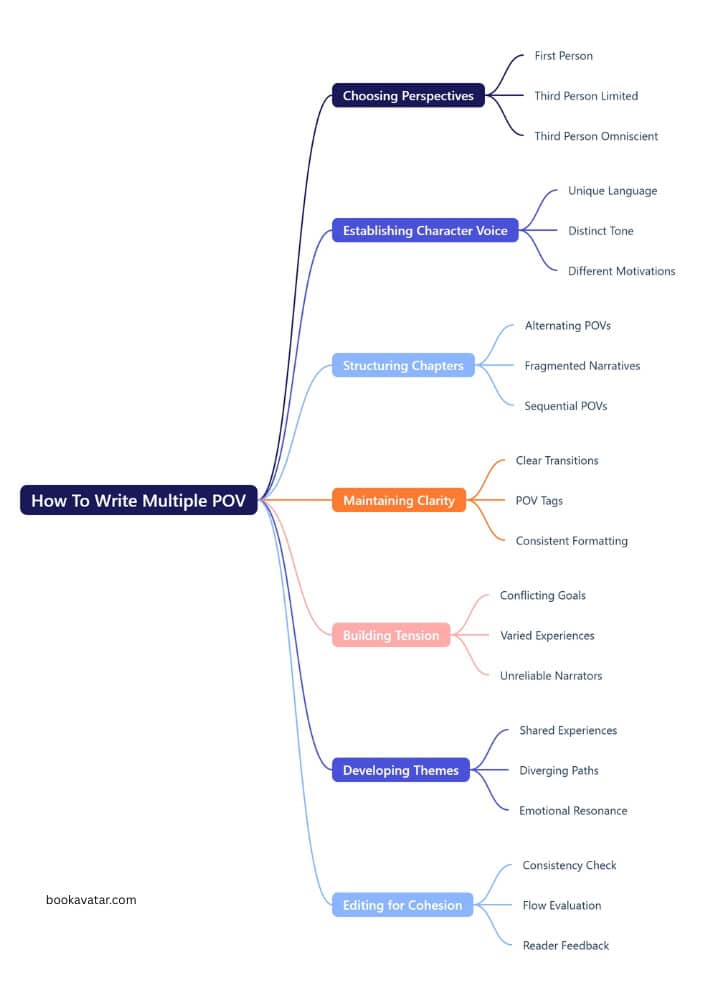

The perspective character will be the character we see the story through. You can have multiple perspective characters. The most typical types of perspective in novels are first person, third limited, and third omniscient. Generally, the more perspectives you have, the more difficult it will be to write. Each character needs their voice, not only in their dialogue but also in the prose and that perspective.

When you’re writing multiple protagonists, their stories will run parallel to each other and affect each other a lot. They both have internal conflicts and, in the end, will have their separate aha moments. But you want to make sure that you balance their stories well. Why do we need multiple perspectives if your characters are all exactly the same? Game of Thrones is the first series that I think of a large cast of characters. Obviously, that world is very involved. A lot went into developing it, and effort went into crafting each individual character. Are you ready for that commitment?

Think about your experience level, how much you want to be challenged, and how much time you want to spend on this project. Even for an experienced writer, it takes a lot of work to do it well. That’s what we’ll break down and discuss in today’s article. So grab a notebook, and let’s get started.

Why do you write multi-perspective?

A story from the multi perspective of different characters helps you to see both sides of the story. Secondly, you can double up on your theme. Chances are your story will have one big overarching theme, but it can also have two different themes based on the truths your protagonists learn from their journeys. I love writing multi-points of views because I write a lot of cute contemporary YA romance, and it’s always nice to see both sides of a relationship and how your couple looks at each other.

The thing about having many protagonists is that they’re constantly interacting with each other, clashing with each other, and affecting each other’s internal and external conflict, which amps up the conflict of your entire story.

Most writers come up with a story idea and write a little bit of an outline or a plot, but they’re focused more on the plot than the characters. It’s where a lot of writers go wrong because they’ll outline the plot and then they run into a wall:

- When should I switch between points of view?

- What does character A think of character B?

- What does character B think of character A?

Should I write the whole story from character A’s point of view and then write the entire story from character B’s point of view? It comes from needing to prepare to write multi/dual points of view.

How to write multiple points of view? (With Example)

A perspective switch is when you swap from one character’s perspective to another. This is done intentionally. If you do three things one, switch perspective, scene by scene, or chapter by chapter, do not switch perspective within a single scene. When you begin a scene with a new character, you need to know whose head you are in.

We don’t know anything that our narrator doesn’t know, and we do not observe things they would not be observing. If you hop around characters’ heads in a single scene, that’s an unintentional perspective switch. Don’t do that. Some people call this head-hopping. It’s an ordinary mark of an amateur, and it detracts from your narrative authority.

As soon as I read an unintentional perspective switch, I want to stop reading. So to pull off a good perspective switch, you need to stick with that character for the whole scene until a new scene or chapter starts. We need to know whose head we are in immediately. Anything other than that is an unintentional perspective switch.

So I have some general tips for writing a novel/story with multiple perspective characters. Let’s begin!

1. Make a character perception map

I recommend outlining your protagonist’s story structures separately and together. All of your characters will have different perceptions of what is going on at every single story beat, whether they’re the ones inflicting the action or the ones with the action being inflicted upon them.

After making each of my characters brief outlines of their side of the story, I combined them to create one coherent three-act story structure. Then I fill it in with more information and emotion to create a detailed outline. It leads to a character perception map, essentially keeping track of what your protagonists perceive at every story beat.

The best place to develop this is within your scene cards. In that scene cards, you will show how you can track not only what your characters say and the consequences of their actions but why it matters and the realizations that your characters have as an effect of the cause. Once you have your three-act story structure, outline, and scene cards ready to go, it’s time to write.

2. Give a healthy chunk of the story

If you have very short scenes and you jump back and forth between characters a lot, that can be jarring. It does take a second for a reader to settle into a new perspective. Doing this occasionally might lead to more tension. It could be stylistic and intentional, but give a good amount of story before you switch characters.

3. Be unique

Each perspective needs to be unique from the other ones. Put a lot of time into developing each character and each narrative voice. It’s very important. You should have only one main character if some are more developed than others. If you have three characters with strong voices, that one’s not a perspective character. You can keep that character in the story, but their voice isn’t strong enough to hold their own.

If you establish a pattern, keep it. If you’re swapping between two perspective characters, keep up with it. If you want a pattern and a list of what’s happening in each chapter, you can ensure the action is spread out. We’re not looking back at a boring character to keep up our pattern. In Game of Thrones, there are so many different characters, and there’s no pattern. It follows wherever the story is. So there are different ways that you can layer multiple perspectives. Figure out what works best for you, and then do it intentionally.

4. Give different struggles for each character

Each perspective character is your main character. They each need their art. If you have multiple perspectives for the sake of storytelling, that’s lazy writing your main characters. Each needs their struggles, own arc, and own voice.

If you only want one main character but need other perspectives to tell the story, some writers will switch between the first and third. So their main character will be in first person, but then we can duck into third person perspectives to see the story from another angle or scenes that first person characters cannot be there for. It can be tricky, but it’s a loophole if you need it.

5. Don’t be afraid to drop a POV character

Sometimes you’ll have an idea for the perspective characters you want, and then whenever you get to outlining or writing, you see that it doesn’t fit. They may seem more like a side characters. They’re only not working as a POV character. If that happens, you don’t need that perspective.

I started Hogan with three perspectives and ended up dropping one of them because being in her head was given a lot of the plot away that I wanted to hide for later. There wasn’t a natural way to have her not thinking about those things. Also, she’s a romantic interest for one of the other main characters. Being in both heads of a romantic pairing makes the romantic subplot much less attractive. So be open to dropping a perspective if you need to.

Quick tips:

- I would recommend giving both your protagonists very opposite personality types, changing the font every time you switch points of view, and assigning specific phrases and linguistic styles to each character.

- Show their direct correlation.

- Always remember your character’s misbelief.

How to shift multiple points of view?

When readers reach a new chapter, they expect a change, and in multi-POV books, that includes the POV change. It can also help create a real page-turner. We switch to another protagonist’s POV when every chapter ends with a reveal, a question, or even a cliffhanger. But we can’t wait to get back to that POV. If you need to switch POVs in the middle of a chapter, you first need a scene break.

Second, there should be movement, as maybe there’s a new setting, a time jump, or the characters are going from point A to point B. If you switch POVs mid-scene without a time jump and without changing settings, that’s dangerously close to head-hopping. For example, let’s say you’re writing a big tense scene between a detective and a suspect in an interrogation room. You’re writing from the detective’s point of view, and she’s pretty positive. This suspect is the murderer she’s been looking for, but she’s not quite sure yet.

So this scene is all about her pulling out all her tricks and trying to get him to confess. The suspect cracks and confesses to the murder, but then we switch POVs. We’re in the suspect’s head. He’s watching this detective gleefully take down his statement of confession. Through his internal narration, we learn that he’s innocent. Something the detective said made him realize that the real murderer was his daughter.

We didn’t switch settings. There’s no time jump. The reader stays present in that scene, but there is a purpose for that POV switch for the detective. So when you’re switching POVs, and you’re trying to figure out where to stop and start those scenes within the timeline of your novel, ask yourself these two questions:

- What’s the moment this character takes action to achieve her goal in this scene?

- What’s this character’s emotional state at the beginning of the scene, and what is it at the end of the scene?

If it’s the same emotion at the beginning of the scene as at the end, then either this scene isn’t finished, or the character doesn’t need a POV scene after all.

Last Words

Repetitiveness is sometimes a good thing when it comes to character names. You want to be repetitive. At the novel’s beginning, your reader is trying to keep all the characters straight in their minds. When you switch it up and call them by their first name, last name, or nickname, you make it harder for the reader to keep track of everything. Pick a name, and use that name and the appropriate pronoun. Keep it simple.

Emphasize this again: check for unintentional perspective switches when you’re editing. Eventually, you’re going to get to a point where you can write without them, and you’ll be able to notice as you make the mistakes. But when you’re editing, check for those.

If you’re a first-person or third-limited POV character who doesn’t know something, your reader does not know it either. You can’t have them look at another character and know what that character is thinking or feeling without being able to observe it. So put yourself in the place of your perspective character and go observation by observation.

Do you prefer to write multiple protagonists or one protagonist? Let me know in the comment below. Happy story writing!

More writing tips:

Table of Contents